The CT simulation takes anywhere from twenty minutes to an hour. The patient lays on the table and the body area being treated is immobilized with either a mask (for head and neck) or a Vac-LokTM cushion filled with Styrofoam beads. When air is removed from the cushion, it creates a unique mold, so that the patient is in the same position for each treatment. The tech also marks the target area with tattoos, guided by laser beams across my abdomen.

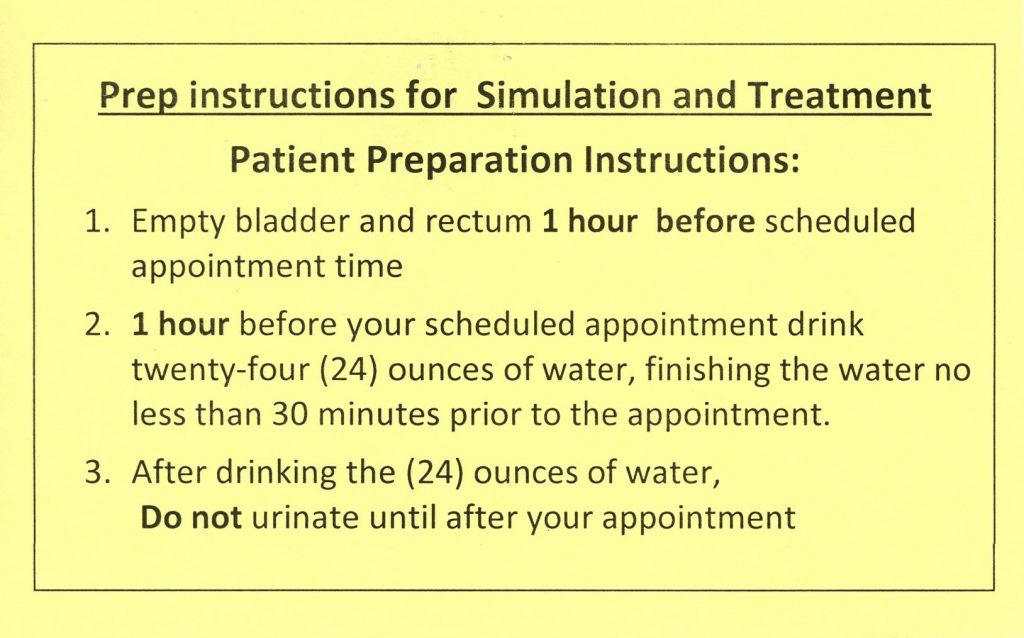

They gave me these instructions to follow before my simulation appointment:

I’m not sure how many people are able to empty their bowels and bladder on command. Everyone’s physiology is unique, so generic instructions like this should be taken as suggestions, not dogma. I used a disposable enema in preparation for the simulation and drank water as ordered. CT appointments were running late, and I had to cross my legs by the time the tech called me.

“Is your bladder full?”

“It’s more than full. My teeth are floating.”

“Well, you’re going to have to hold it for at least 20 minutes. Do you think you can do that?”

“Oh, hell no!”

“Well, empty your bladder a little bit but not too much.”

That’s easy for you to say…

The CT simulator room was down a long hallway past steel double doors and far from the treatment rooms. The tech placed what looked like a heavy, vinyl sleeping bag on the bottom half of the simulator table before I lay down. A few minutes later I felt the Vac-LokTM bag harden around my legs. The tech left the room after all was set, and all I had to do was lie back and think of England for the next 20 minutes.

When the scan was finished, she made three cross marks with an ink pen – one in the middle of my lower abdomen and one near each hip – and covered them with waterproof tape. I’d get permanent tattoos at my first treatment. Before I got off the table, she took my picture with a small digital camera. My DMV mugshot looks like a Rembrandt portrait in comparison.

A radiation physicist and/or medical dosimetrist uses the information acquired by the scan to calculate radiation doses, precise target locations and the number of daily treatments required. This can take a few days or a couple of weeks. (I also think they use the time to ensure treatment is covered.) Treatment starts after the radiation oncologist approves the plan.

I got the call on January 24 to start treatment the following Monday.

The Radiation Oncology treatment center runs about 80 patients through two rooms every day. New patients are fitted into available slots for the first week or two; they get a regular appointment time as other patients complete their treatments and leave. My appointments were anywhere from 1:15pm to 4:15pm before getting a 12:30 slot at the end of week 2. This was a great time because there were more available parking spots near the entrance.

On Monday I arrived 15 minutes before my appointment only to find my first treatment session was cancelled because of some issue with the machine. Carla explained someone had called me, but I didn’t recognize the number and had ignored it. (Note to self: add important number to your contacts.) She assured me their technical people were working on it and I should be able to start the following day.

Peg had gone into work, so she called to ask for an update.

“So how did your first session go?”

“It didn’t. The machine was broken.”

“What happened?”

“Well, it got stuck and the guy who was in there got a massive radiation dose and he exploded all over the place. There are guts on the wall, and they had to bring in a hazmat team to clean it up.”

“WHAT? Oh my God! That poor man! I can see where they’d need hazmat with all that radiation…Wait, did that really happen?”

Me snickering on the other end.

“You’re an asshole.”

On Tuesday Radiation Oncology called me just as I was getting ready to leave.

“We’re still having problems with the machine, and they are waiting for a part.”

“What, STILL??? So, I’m going to have to wait another day?”

“No, we are trying to work people in. Can you come for a treatment at 4:15 today?”

“Yeah, that will work.”

Not as if I have a choice.

Peg was livid when I told her.

“It’s not a problem for you; you’re retired, and it’s only a 15-minute drive for you. What if it was someone who was working and had to arrange time off? Or someone who had to drive 30 or 40 miles to get to their treatment? If we have a problem with our computer system, someone is on it right away! If this is going to be a regular occurrence, we might have to think about going to one of their other facilities that is more reliable for your treatment!”

Carla took me back to the treatment area for the first time and showed me the locker room. After that, I was allowed to pass GO and head back on my own. There were separate locker and waiting rooms for men and women, not unexpected since most patients wore hospital gowns to expose their treatment areas.

The flat-panel TV on the wall drowned out the overhead speaker playing classic pop music from the 1960s to the 1980s, appropriate for our ages. There was a rotating collection of old guys in the waiting room during my first week; we recognized our arrivals with nods or grunts while watching Bonanza and Rifleman reruns. Several times one man sat in the corner reading a book. I assumed he was there supporting his wife since no one ever called him back for treatment.

Mostly we kept to ourselves, but one day an older man started talking to me about his disease. I wasn’t sure what to say so I just listened.

“I had prostate cancer and now it’s in my bones. They did this procedure (therapeutic plasma exchange) where they take your blood out and clean it and put it back in and that’s helped a lot with the pain.”

He seemed far less upset than I might have been, but maybe that’s part of getting older. You’re resigned to the things you can’t really change and just hope the eventual end isn’t terribly painful.

I couldn’t have any metal (rivets, buttons, zippers) near the treatment zone, so in the beginning I changed out of my jeans and put on a hospital gown. By the third week I’d learned to wear sweatpants and slip-on shoes after seeing another guy wearing them. One might figure they’d make that suggestion to patients, but one would be mistaken.) I’d toss my jacket, car keys and shoes into the locker and was ready to go.

I played around with the amount of water and the time when I started to drink. I learned not to eat a Reuben just before drinking because the fat slowed down water absorption. I tried drinking a lot more than usual to get my bladder to fill, but I paid the price when I peed like a racehorse for a couple of hours, long after my treatment ended.

I started wearing Depends because it was difficult to fill my bladder enough to keep the techs happy but not so full that I might leak. One time the tech, a young guy probably in his 20s, told me my bladder wasn’t full enough and I should drink more water before the next treatment. (That’s easy for you to say.) I’d gotten the sudden onset of explosive diarrhea right before my session and unless I clamped the hose with a chip clip, my bladder was going to be on the dry side.

My routine: Every day the techs call my name and escort me to a long desk on which sat several computer screens. Each time they ask for my name and date of birth, which I think is a bit silly. They know my name, my picture is on the computer screen, and I can’t imagine why anyone would sneak into radiation treatments for the hell of it.

There are three large signs above the entrance – HDR, BEAM and XRAY – which illuminate depending on which process is active. The department uses high dose radioisotopes (HDR) such as iodine-131 (I-131) for treating thyroid cancer. I’m getting Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT) which uses higher doses of x-rays (BEAM). XRAY lights up when doing a CT scan, a much lower dose, before treatment.

I walk in past a 10” thick door filled with lead and into a lead lined treatment room. When I told Peg about the lead, she said, “See! The chances of a disaster are low but not zero!”

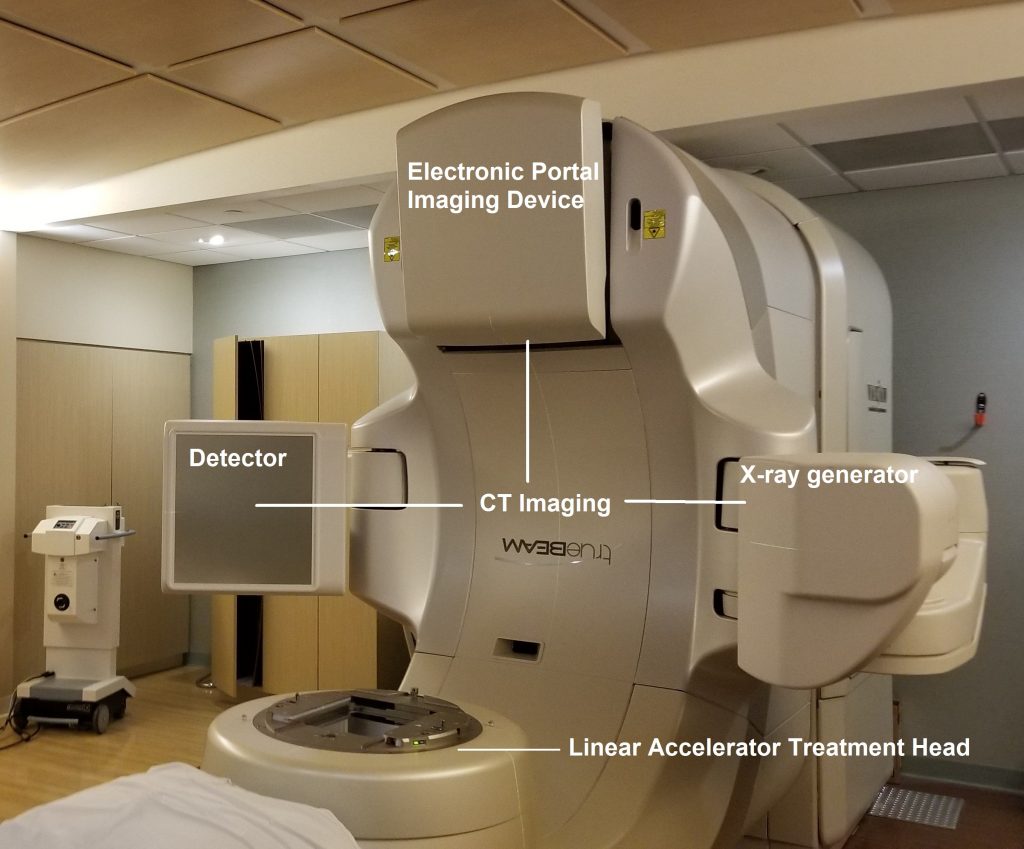

The star of the show is the Varian TrueBeamTM Linear Accelerator. The kV x-ray generator and flat panel detector are at 3 and 9 o’clock. The Electronic Portal Imaging Device (EPID) is at 12 o’clock. The linear accelerator treatment head is at 6 o’clock.

I drop my pants and jump on the table, putting my legs in the Vac-Lok mold. They ask if I want a blanket, but I decline because it’s warm in the room. They are quick to cover my nether regions with a pillowcase, but I think it’s for their peace of mind more than mine. Old man penis, like its owner, is tired and not much to look at. Laying on my back is uncomfortable. I’m trying to keep my bladder from leaking, and my right shoulder hurts when I put my arms above my head. I just want to get it over with.

They raise the table and push it towards the machine. They still need to adjust my body by yanking on the sheet beneath me. “Pull a quarter. Pull a half. Pull one.” When the lasers are lined up with my tattoos, they leave the room. I hear the door creaking as it closes, and I wait.

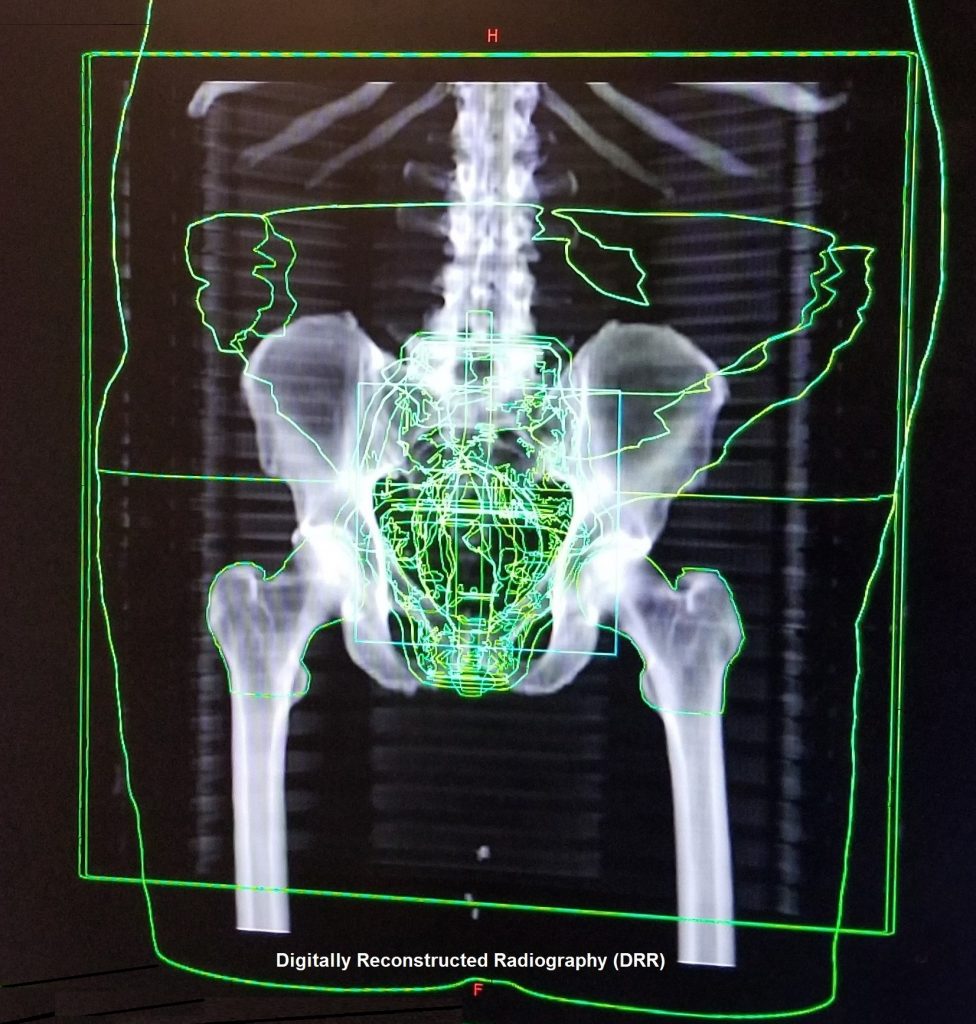

The CT parts move into position. The machine then makes a single smooth rotation and forms a CT image of my pelvis which appears on the computer screens at the desk. Then the tech compares a digitally reconstructed radiograph (DRR) with the scan for fine alignment. The scanner parts are moved back to their resting positions, and I wait while things are lined up. Sometimes the tech remotely adjusts the table before the treatment begins.

There’s a dull thud a few minutes later which I assume is the accelerator powering up. A red light on the wall starts flashing. There’s another thud followed by what sounds like a swarm of cicadas as the machine starts to rotate. This time the machine’s movement is a little jerky. (Dr. Howard told me that happens as the collimators in the treatment head adjust, shaping the treatment beam.) It makes one full rotation, pauses for six seconds and then rotates in the opposite direction.

Occasionally the machine will stop and beep. They told me afterwards not to worry, because automatic sensors stop it if the sheet got too close, and no, it wasn’t continuing to fry my innards. They had to reboot the computer system during another treatment. You’re sure everything is OK out there?

The machine stops and I can hear the blast door opening. The techs lower the table as I pull up my pants. They remove the mold and help me sit up. I say, “See you tomorrow.” Then I make a beeline for the bathroom.

Every Tuesday they take my weight, and then Danielle escorts me to an exam room and asks me the following questions:

“How are you feeling?”

“Pretty good.”

“Any problem with diarrhea?”

“Not enough to need Imodium.”

“Any problem with urination?”

“Nope.”

“How’s your energy level?”

“It sucks.”

“OK, I’ll tell Dr. Howard you’re ready.”

Some side effects can be debilitating. A friend of ours, who is really skinny, suffered radiation burns to his lower abdomen that were so painful his wife had to drive him to his appointments lying flat in the car. The mother of someone with whom Peg works has to drive 40 minutes to her sessions and sometimes is so tired she can barely get out of bed.

Diarrhea has been the worst side effect. I initially thought it was because I no longer had a gall bladder, but it was much worse than that. The first bowel movement of the morning is normal; after that it’s watery like my colonoscopy prep. I can hear my intestines gurgling and I get sudden urges for the next few hours.

Fatigue has been the most frustrating. I have a long list of things I’ve wanted to do since I retired, but motivation is near impossible. I want to nap all the time, but I fight the urge, which does me little good. I’m still tired and nothing gets accomplished.

Dr. Howard comes into the room a few minutes later and goes over what the nurse has told him. I verify my answers for him, and he says, “You are doing remarkably well. I’ll see you next week.”

During one visit I asked him, “What’s the chance of recurrence?”

“Let me look at your pathology report.”

“Gleason 9 with EPE (extraprostatic extension.”

“Yes…I think we have an 80-85% chance of cure.”

This wasn’t surprising given my tumor was aggressive. If I’m lucky, any recurrence will be slow and late enough that something else will kill me first.

My visits with Dr. Howard are short because I am a physician and not a typical patient. We speak the same professional language and have an intuitive understanding of each other. (Peg says we share “the secret handshake” that grants me access to special courtesies like being released from the hospital three hours after my prostate surgery.) I’ve had very few side effects and there is little need to spend a lot of time with me.

Lest you think the physician visit is superfluous and merely a reason to charge for the visit, I can assure you it’s not. He or she is monitoring a patient’s progress and needs to be aware of anything that might require altering the treatment plan.

The average patient is likely to be overwhelmed with a cancer diagnosis and subsequent treatment. Nurses have a special role as the intermediary. Patients will often impart far more information to the nurse because “I don’t want to bother the doctor.” They pick up on a patient’s non-verbal cues such as reluctance, anxiety, frustration, or anger. And it’s not unusual for a patient to tell the nurse one thing and the physician something entirely different or contradictory.

I got a garden-variety cold the last week of treatment and I was far more tired than usual. (I suspect it’s because my niece had one the week before me. She is a pre-school nurse, and her charges are disease-spreading vermin who rarely suffer as much as adults with the same maladies.) As I left the treatment room the second to last day I said to the tech, “I’d like to say I’m gonna miss this but I’m not.”

Finally, it was over. I dragged my tired ass out of the locker room and rang the large bell sitting at the desk, signaling the end of treatment. I said goodbye to Danielle and hugged Carla on the way out. The staff was great, and I can’t thank them enough.

It’s been a few weeks since I finished treatment. The diarrhea has slowly gotten better, but I still have a throbbing, painful hemorrhoid reminding me every day. I’m less tired which may be due to more sunny weather as well as recovery.

I’ll get my first post-radiation PSA and see Dr. Howard at the end of June. It probably won’t be down to zero because radiation therapy isn’t like a laser blasting everything in its path. Instead, it kills some cells and damages the DNA of others so those cells can’t replicate. (How Radiation Therapy Treats Cancer-NCI)

I’ll discuss the aggravation of dealing with billing in another post, but the ballpark estimate of charges for my treatment is around $69,000.

Featured image © Can Stock Photo / focalpoint