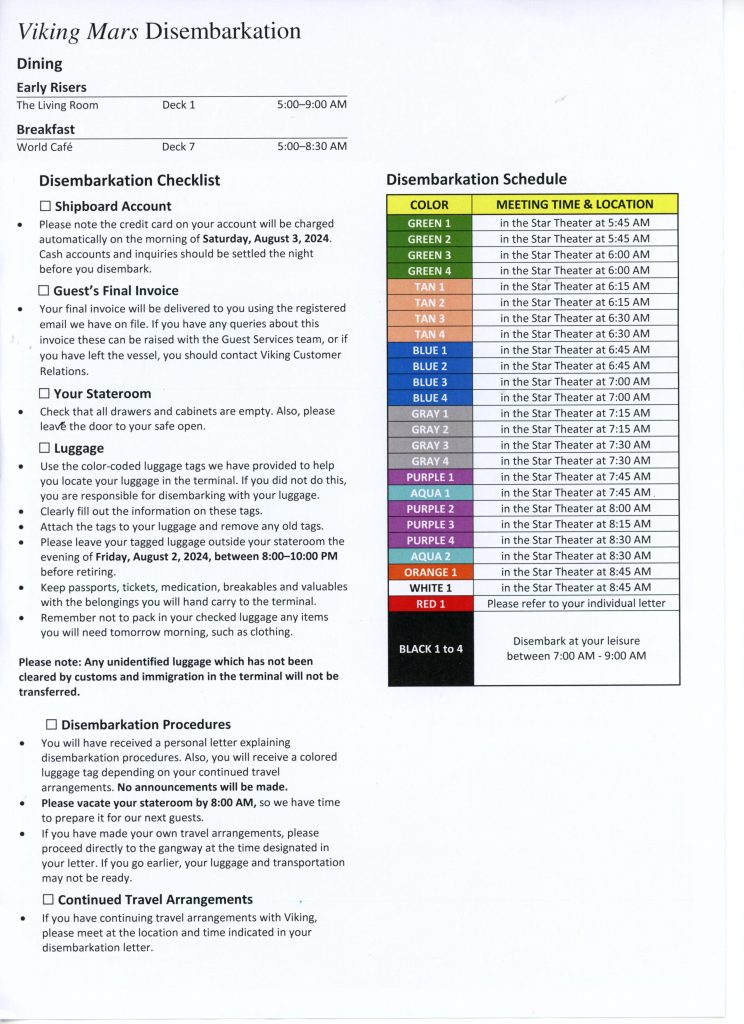

We made it to the Star Theater, our assigned assembly area, just as the group before us was leaving. When our turn arrived, we followed the path outside to the checkout station, scanned our cards and bid a bittersweet farewell to the Viking Mars. Not really. We’d gotten up earlier than usual and I hadn’t had my coffee, but I wasn’t awake enough to notice.

The sun was out, and the sky was a deep blue…which was just our luck. Our arrival and departure days were the only ones without clouds and rain. We walked down the gangway and into a tent, quickly identified our luggage, and then headed toward our assigned bus indicated by a staff member at the end of the tent, the same woman who guided the Southern Coast of Iceland tour. We settled into seats in the front row, waited for everyone to finish boarding and then departed on Reykjanesbraut, the highway to Keflavik International Airport. Click here for a short clip of the trip..

Ours was one of several buses lined up to discharge passengers at Keflavik. We waited while the driver unloaded suitcases, grabbed ours and headed for a very crowded entrance. I recognized the taxi pick-up area just to our left, remembering the dickhead that commandeered a van that could have held seven people just for himself.

Our arrival had been a challenge; our departure was absolute pandemonium. (The planned expansion, expected to be completed by 2030, can’t come too soon!) The airport has self-service kiosks for check-in, but one still needs to hand over tagged bags to an agent. I’d guess there were at least a few hundred people crammed into the lines that were moving like glaciers. Peg sat down at a small area reserved for wheelchair requests while I debated getting in line. I noticed the Icelandair Premium counter, at the far end of the perpendicular wall, was almost deserted. I grabbed Peg, our suitcases and passports and headed there; we were checked in and done in five minutes. There were several older women sitting in the wheelchair pickup area when we returned. One of the staff asked, in English, who needed a wheelchair. While the others looked around at each other in apparent confusion, I got her attention. If you snooze, you lose, and this was going to be one very long day.

The staffer was a Nordic goddess! Tall, blond hair, blue eyes and a butt to die for; she was a sight to behold even if I was old enough to be her father (or grandfather). I put my eyes back into my head and followed her as she deftly cut through the crowd, heading for the elevator that would take us to the second floor. People in wheelchairs get access to a priority line with far fewer passengers at the security checkpoint. When we arrived, I put Peg’s carry-on onto the conveyor belt, and we went through the metal detector.

We hadn’t removed our Kindles from the bag—it’s never been a problem in US airports—but they triggered the screener to flag it. This type of scanner automatically pushes suspect luggage onto a parallel conveyor belt for further inspection. A second screener grabbed Peg’s bag, put it on a long table behind her and asked, “Whose bag is this?” We both raised our hands.

She went through the bag and pulled out our Kindles. “These have to go through separately.” She put them in a plastic bin and ran our bag and the Kindles through again. We had to show her our boarding passes to reclaim the bag.

Peg’s carry-on bag wasn’t the only thing we picked up. A couple of disease vectors (read: little kids with underdeveloped senses of hygiene) were coughing openly and sniveling in our vicinity. I hadn’t thought of bringing masks, but I should have. We were in another country among a novel pool of viruses for which we had no immunity, and we both developed upper respiratory infections two days after our return.

Getting a wheelchair had another advantage. Instead of continuing with the mass of humanity headed for the gates, our Nordic goddess made a right turn and headed for a controlled access door that took us directly to the concourse leading to the South Terminal and the only lounge in the airport–available only to business/first-class passengers–where we would hang out for the next several hours.

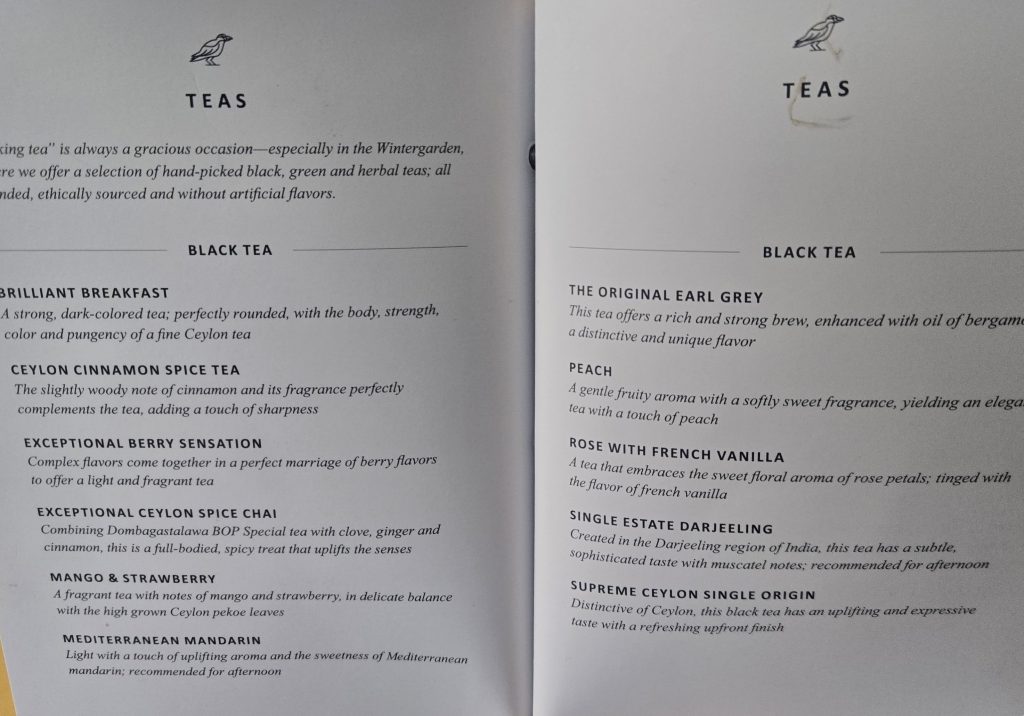

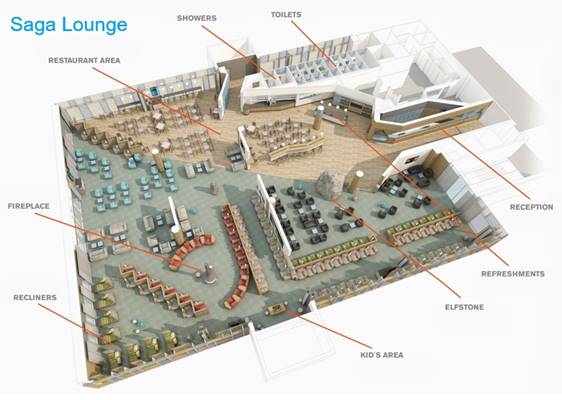

Icelandair’s Saga Lounge is on the South Terminal’s third floor, away from the chaos, and is spectacular! We showed our boarding passes at the reception desk and then explored the area, passing by the self-serve buffet and restaurant seating that put food kiosks for mere mortals to shame. I saw a large smoked salmon, yogurt, granola, hot and cold cereals, and pastries. Drinks included water, coffee and tea, sodas, and a variety of alcoholic spirits, most notably 64° Reykjavik Distillery’s Rhubarb and Angelica Pink gins. The buffet switched over to lunch selections – a salad bar, hot soup, meat and cheeses for sandwiches, and cookies – around 11am.

A large boulder, an “elfstone”, sat at the entrance to a seating area across from the buffet, with leather chairs and loveseats around small coffee tables. I can only imagine how they got the rock into the lounge and hoped the engineers had correctly calculated sufficient floor support.

We found a spacious lounge area behind the elfstone section with wide, comfortable surrounding a gas fireplace in the center. Small tables with USB ports and European outlets separated the chairs, providing room for drinks and personal belongings. Chaise lounges located along several of the full-length windows afforded guests views of the peninsula. Strategically placed refreshment stands featured refrigerators with cold soft drinks, an automated coffee/cappuccino maker with real china cups, and a variety of alcoholic spirits. We parked Peg’s rollator and carry-on at one end of the chairs and headed to the buffet for breakfast.

The bathrooms behind the restaurant are remarkable. The lighting is indirect and soft; none of the fluorescent glare in most public toilets in the US. The floor and sinks are immaculate, and the stalls have full-sized doors. The toilets are wall-mounted, which makes cleaning the floor a lot easier. Two shower rooms equipped with soap, shampoo, conditioner, and large towels are available without needing a reservation. (You’ll know what I mean if you’ve ever been in a large, interstate truck stop.)

We returned to our seats after breakfast. Most of the next several hours were quiet, aside from the horde of eight-year-old girls running amok until they left for their flight. A woman sitting near us kept bitching at her teenage son’s dietary choices. I made several trips to the refreshment bar refrigerator to replenish Peg’s drinks. We later revisited the food area for lunch; I had a few shots of the rhubarb gin during the afternoon.

The reception desk had assured us the wheelchair escort would return around 5:00pm for our flight, but no one had shown up by 5:45 so we had the desk call for someone. It took about 30 minutes for the escort to arrive, and boarding had already started when we reached the gate. There’s no seating at the boarding gate and hanging around would have been another nightmare. We had to take an elevator to the jet bridge while the more mobile had to climb stairs. We gate-checked Peg’s rollator, assuming it would be at the gate at O’Hare when we arrived, another mistaken assumption.

Our flight back was uneventful. We once again had drinks and dinner and settled in. First class passengers get free noise cancelling headphones, so I browsed music by Icelandic composers—I think Norwegian and Finnish composers are better)—while Peg watched the Barbie movie. Despite leaving Iceland at 7:00pm, it was just dusk as we descended over Michigan on our way to O’Hare. We were more than ready to get off the plane by the time we landed.

We hadn’t seen passengers getting off the inbound flight the night we left. We discovered that international passengers are diverted to Customs instead of walking past the boarding area, a VERY LONG trek. Peg’s rollator wasn’t at the gate (big surprise), but a wheelchair was ready. We went down a corridor, down a long switchback ramp to the ground floor and then another long walk before standing in yet ANOTHER line to pass through Customs. (O’Hare might want to consider installing a moving walkway.)

We were exhausted but fortunately had a young and friendly Customs agent to whom we presented our passports.

“Do you have anything to declare?”

“A couple of chocolate bars for the family.”

“Well, you look OK. Have a good night.”

We walked through the checkpoint to baggage claim, found our bags and the Rollator, and headed outside. It was warm and muggy, unlike the cool and cloudy weather we’d left behind. I called for our pickup and waited for 20 minutes until he arrived. We piled into the car; the air conditioning felt really good. The driver and Peg chatted; I pretended to sleep. Finally, we were home and ready to crash, but I had to turn the water back on. A quick trip to the basement and then bedtime!

The cruise was a good way to get an overview of Iceland with minimal hassle. If we were to do it again I’d wait a few years until Keflavik International Airport has been renovated, and I’d rent a car so we could see things at a far more leisurely pace than the tour bus cattle herding. We’d definitely want to revisit Akureyri; it’s a five-hour drive from Reykjavik but a 45-minute flight from the downtown Reykjavik Domestic Airport.

Time is becoming a scarce commodity and the current political turmoil threatens international travel. I’m just grateful we were able to make the trip.

Up Next: Postscripts

Photo Credits:

Beautiful sunset in Iceland II. Helgi Halldórsson from Reykjavík, Iceland. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

Saga Lounge graphic: Icelandair.com

All other photos: mine.