When I was in medical school an instructor admitted, “Half of what we teach you is wrong. The problem is, we don’t know which half.” I could say the same about residency. Some of what I learned as an intern fell out of favor by the time I was a chief resident, such as x-ray pelvimetry to determine a woman’s likelihood of delivering vaginally, or the internist’s casual approach to glucose control in diabetic pregnant women.

The pendulum continued to swing over the next thirty some years of my career. We went from “Once a (Cesarean) section, always a section,” to “Every woman should be offered the chance to deliver vaginally after a Cesarean,” to “Let’s put a little thought into who should be doing this!”

I did a rotating internship after medical school because I had no idea which direction I should take. Obstetrics was the last thing on my mind because the physician with whom I had the most contact could be sarcastic and demeaning. That changed during two months of obstetrics in a completely different environment. I ended up taking the second-year position vacated by one of the first-year obstetrical residents who left to fulfill his three-year obligation to the U.S. Air Force. (I heard he went into radiology when he got back.)

Fast forward three decades. I was working as a locum tenens physician for the medical school I’d once attended. My old obstetrical tormentor had retired from practice but continued to be heavily involved in student and resident teaching. The years had mellowed him, or maybe it was because he didn’t have the stress and burden of a private practice.

One afternoon he asked to join me while I was doing an abdominal hysterectomy. I doubt that he remembered me from so long ago, but I was honored that he’d ask and was truly interested in what I was doing. The circle was completing; the student was now the master and the master was now “master emeritus.” Side note: I’ve never been cocky enough to consider myself a “master.”

A few months ago, I met a delightful young medical student doing her obstetrical rotation. She is intelligent, capable, ambitious and learns quickly. She began her first year as an ob/gyn resident in July, which has prompted me to reflect on what has changed since I was the youngster under the gaze of my mentors, some of whom were approaching retirement.

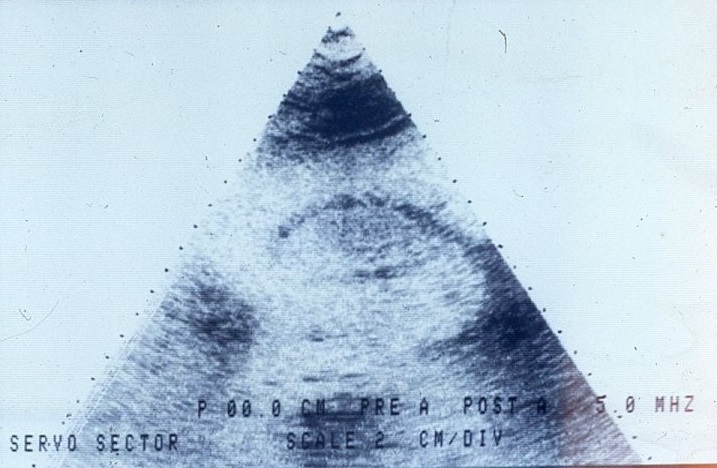

Ultrasound: Ultrasound has been around since the early 1960s, but the first images looked more like abstract paintings than recognizable body parts. The ultrasound tech would swipe the transducer – a thing about the size of a restaurant salt shaker – that sent and received sound waves – back and forth across a woman’s abdomen. The results looked like this:

I couldn’t tell you what this was, and we suspected neither could most radiologists. More than once we would explore a woman’s abdomen because a radiologist swore “there is definitely an ectopic pregnancy present,” and find nothing.

Ultrasound has evolved. Machines can produce three dimensional images in real time, check on blood flow into and out of organs and measure minute structures in developing fetuses. Emergency departments now have FAST ultrasounds (Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma) which can rapidly detect internal bleeding or a pneumothorax (collapsed lung) at the bedside, obviating the need for a CT scan. It’s much better than the old way of diagnosing a ruptured tubal pregnancy, which was sticking an 18-gauge needle through the posterior vagina into the pelvic cavity looking for non-clotting blood.

Gonorrhea testing: Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the bacterium causing gonococcal infections, grows best within an oxygen-poor environment. We used to take a sample from a woman’s cervix, smear it across a culture plate, then stick it in a one-gallon pickle jar with a lit candle and close the lid, burning off the oxygen. By the end of the day we’d have 20 or so culture plates in the jar and the room would smell like burnt wax. Now we look for gonorrhea (and chlamydia) DNA on a cervical swab or in a urine sample.

Fetal monitors and intrauterine pressure catheters: Fetal monitors, which track a baby’s heart rate and a mother’s contractions, were introduced in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Both were accomplished with devices placed on the mother’s abdomen, but the results often were inaccurate. The scalp electrode, created in 1972 by the venerable Dr. Ed Hon, allows us to monitor the baby’s heart directly.

The modern intrauterine pressure catheter (IUPC) measures contractions through a solid, transducer-tipped catheter threaded into the uterine cavity. The early catheters were fluid-filled tubes connected to a small strain gauge transducer which required a dome of water placed directly on the pickup before the cover was screwed on. The transducer then had to be taped to the bed rail at approximately the same height as the uterus. Sometimes we’d use a tongue depressor and thick adhesive tape to keep it in place. Then we’d open a stopcock to “zero out” the system, close the stopcock and hoped it all worked.

Determining ruptured membranes: Back in the old days we determined if a woman had “broken her water” by inspecting the vagina with a speculum for amniotic fluid, testing any visible fluid with nitrazine paper, and then slapping some fluid on a slide, letting it dry and look through the microscope for “ferning.” If there was any question, we’d have the woman wear a pad and check for fluid an hour or so later, or, in rare cases, inject indigo carmine dye into the uterine cavity and look for blue fluid in the vagina. When ultrasound came into widespread use, we looked at fluid levels around the baby.

Then a company created an expensive test to check for an amniotic fluid protein to determine whether membranes had ruptured. Their ad campaign preyed on all our fears by asking, “Are you really, really, absolutely, positively sure?” Hospital administrators took away our nitrazine paper and microscopes because now they had a test for which they could bill. Doctors liked it because it meant they didn’t have to stagger out of bed in the middle of the night to do an exam, or so they thought.

Then in August 2018 the FDA issued an alert reminding physicians “that the labeling for these tests specifies that they should not be used on their own to independently diagnose…ROM (rupture of membranes) in pregnant women.”

A Korean study found a positive test in a third of women in labor with intact membranes. A review of ROM testing published in The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of Canada was cautiously optimistic about protein assays although they cautioned “Further studies are needed to assess the reliability of the test according to the time from membrane rupture.” So what would make the critics happy?

We do our best, but nothing is perfect.

Hysterectomy: Vaginal hysterectomy has been compared to rebuilding an engine through the tailpipe. The Grand Old Man of vaginal hysterectomies attached to my residency program retired during my second year, so I learned to take out uteri through an abdominal incision. Not that I couldn’t do a vaginal hysterectomy, but I liked being able to see what I was doing. Few things are worse than fishing for a bleeding artery through a vagina.

Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) started to become popular in the 1990s, but the learning curve was steep. I knew physicians who spent seven hours on their first few LAVHs after going to a weekend course, which is no substitution for extensive residency training.

The alleged advantage of LAVH was being able to detach the tubes and ovaries under direct visualization, but one still had to finish the procedure vaginally. Most of the required equipment was disposable and expensive, making it 40% more expensive than a traditional vaginal hysterectomy. Some of us thought LAVH made up for a lack of skill.

Robotic surgery started becoming popular in the early 2000s, but robots were used more for marketing than for patient benefit, and they weren’t cheap. A robot cost $1-$2.5 million up front and came with a $100,000 to $170,000 annual service contract , enough to give any hospital bean counter palpitations.

But, after years of experience and refinement, doing a hysterectomy exclusively with laparoscopic equipment made total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) a truly “minimally invasive surgery.” One surgical assistant told me taking the detached uterus out at the end was like uncorking a bottle. More than one study found there was no advantage to using robotics over TLH. I suspect many of those machines will be gathering dust in closets, sitting next to $100,000 carbon dioxide lasers used to treat precancerous cervical lesions before LEEP (wire-loop cautery used to whack out a chunk of cervix) became popular.

Employment: Physicians were masters of their domains for most of the twentieth century. In the early days, you graduated from medical school, did a year internship to get a license and hung out a shingle as a general practitioner. Specialties (and specialty boards) started appearing during the 1950s, along with residency programs lasting three to seven years, and the old GP would become extinct. Physician practices were still largely independent even into the 1990s. Being employed by a hospital or, worse yet, a “goddam HMO” made you a substandard physician who couldn’t get a job anywhere else in the eyes of the Great White Fathers who still ran things.

But, as I’ve previously discussed, things have changed. By 2017 less than half of American physicians owned their own practices, especially in metropolitan areas. I live in the Chicago suburbs where a large majority of private practices have been absorbed by large medical groups and/or hospitals. New physicians expect to be employed rather than deal with the headaches inherent in independent practices: personnel, equipment, rent, taxes and liability insurance, which can run $150,000 a year for an ob/gyn. We gave up autonomy for financial security and lost both in the process.

Patient care and ownership: The generation of physicians before me cringed when administrators used terms like “customer service,” but in their hearts they knew what it meant. They took good care of their patients because those patients were their livelihood. In a group practice the patients were all OUR patients, rather than MY patients and YOUR patients.

Primary care developed “concierge care” as a backlash to corporate medicine. Concierge care promises same day or next day appointments, access to one’s physician 24/7, unhurried visits and “personalized care,” or what I used to know as “doing my damn job!” I’ve called patients with test results, talked to them at all hours of the night and I made at least one house call to check on a patient’s Cesarean section incision that had opened up.

This “white-glove customer service” comes with annual fees ranging from $1000 to a whopping $25,000! And that is just for the privilege. Actual care still costs money. You can’t use Flexible Savings Account (FSA) or Health Savings Account (HSA) money for the fee, so this isn’t an option practical for the masses.

I’d like to think there’s a new generation of physicians willing to fix what’s broken for everyone, but I’m not holding my breath.

Thanks for the memories.

I am there with you through the years of change both as a coworker & a patient…

That’s a historic reading experience. Makes me feel ancient. Personally, I was thrilled to have repeat C-sections, that labor experience was nothing I wanted to experience again. LOL 😂

So interesting! Things change so rapidly that I don’t know how Physicians keep up!