There is a lot of misinformation and bad advice circulating regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. I’ve tried to provide pertinent and useful information in this blog post. But before I begin, I want you to do two things:

DON’T PANIC

DON’T BE STUPID

Panicking in a crisis does no one any earthly good and often makes things worse. This is not the zombie apocalypse, Outbreak, The Stand, Contagion or The Walking Dead. It’s not even The Hot Zone, a book and miniseries based on the discovery of an non-human primate Ebola virus in Reston, VA in 1989.

We can get through this by helping each other, not by being a selfish asshole hoarding toilet paper, or going out to restaurants because Devin Nunes told you to. Follow current recommendations and guidelines to minimize the risk of getting it or giving it to someone who is at greater risk of dying.

Now, back to our previously scheduled PSA

What is Coronavirus?

Coronavirus is a family of RNA viruses – chunks of genetic material in a protein capsule – that infect human respiratory tracts. Coronavirus, like the more well-known rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and parainfluenza, often cause nothing more than a common cold. It is so named because there are spikes on the surface that make it look like a solar corona. Click here to see an electron micrograph.

Where did it come from?

Coronaviruses are “zoonotic” – transferred from animals to humans. Bats provide a reservoir for coronaviruses and spread them to other animals. SARS was thought to come from civet cats in Guangdong, China, while MERS was transmitted by dromedary camels in the Arabian peninsula before spreading to other countries. (MERS resurfaced in Saudi Arabia in October 2019.) SARS-CoV-2 might have originated from an outdoor wet market in Wuhan, China. Neither the Chinese nor the United States developed it as a bioweapon.

How is it spread?

Coronavirus, like other respiratory viruses, spreads among people through droplets from coughing or sneezing which are then inhaled. It can also spread when hands contaminated with virus touch eyes or nose, or someone else’s hands.

The incubation period (time from contact to developing symptoms) is 5-7 days but can be as long as 14 days, the rationale for a 2-week quarantine. People who carry the virus can spread it even though they feel fine. Health officials estimated a lawyer with COVID-19 in New Rochelle, NY, had contact with 50 people before becoming ill.

No one is sure how long the virus survives on surfaces like countertops, handrails and boxes, although study results published in the New England Journal of Medicine on March 17, 2020 found coronavirus lasts longer on plastic and stainless steel than on copper and cardboard. When in doubt, wear gloves and wipe it off!

VIDEO: Amanpour & Co. Infectious Disease Expert Dr. W. Ian Lipkin Discusses How Coronavirus Spreads

If coronavirus is common, why should I worry?

Viruses, like bacteria, can mutate into more deadly forms. The virus causing the current disease, COVID-19, is severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Yes SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome 2003) and MERS (Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (2012) were both “novel human coronaviruses,” meaning they hadn’t been seen in humans. The difference between coronavirus causing a cold and SARS-CoV-2 is like the difference between the E. coli in your intestine and E. coli O157:H7. The former keeps your digestive tract healthy while the latter caused severe illnesses and deaths in people eating contaminated hamburger (1993), “organic” spinach (2006) and Romaine lettuce (2019).

Isn’t it just like getting influenza?

There have been an estimated 34 million influenza infections in the United States over the six-month 2019-2020 season with 375,000 hospitalizations and 22,000 deaths. But we have a vaccine and herd immunity for influenza, so the death rate is about 0.06%. There is no vaccine for COVID-19 and there won’t be one for 18 months or more. COVID-19 is more likely to kill people over 60, those with chronic illnesses (diabetes, asthma/COPD, heart or chronic kidney disease), and anyone with compromised immune systems (cancer, HIV, genetic disorders), regardless of age. The youngest death was a 21-year-old Spanish soccer player with undiagnosed leukemia and coronavirus.

As of March 17, 2020, there have been 197,320 cases of coronavirus and 7,950 deaths around the world. (Source: Worldometer Live Update-Coronavirus) That doesn’t sound like much until you do the math, which gives you a death rate of 4%. The New York Times reported C.D.C.’s worst case scenario:

“…Between 160 million and 214 million people in the United States could be infected over the course of the epidemic, according to a projection that encompasses the range of the four scenarios. That could last months or even over a year, with infections concentrated in shorter periods, staggered across time in different communities, experts said. As many as 200,000 to 1.7 million people could die….”

Take a deep breath and don’t panic. England got through WWII with “Keep Calm and Carry On,” not, “OMG, it’s the apocalypse and I’m going to run out of toilet paper!”

Related: USA Today What does the coronavirus do to your body?

How do I keep from getting COVID-19?

- Wash your hands, often! Wash them for 20 seconds, the time it takes to sing “Happy Birthday” twice or recite the Star Trek intro. Hot water isn’t more effective than cold or warm water, so don’t scald yourself.

- Use hand sanitizer if you’re out and don’t have soap. Antibacterial wipes are good for public surfaces (shopping carts, handrails).

- Don’t touch your face. That is going to be really hard for most people. Cajun hand sanitizer will make you remember not to touch your face!

- Although it’s better than using your hand, I don’t think coughing or sneezing into your elbow is a great idea. Get a small pack of tissues or stuff some in a zip-lock bag and keep them handy when out. Use them and toss them in the trash. And use hand sanitizer afterwards.

- Stay away from crowded places like subways, commuter trains and airplanes unless absolutely necessary. Many businesses are making their employees work from home.

If you need catchy music to grab your attention, then watch this Vietnamese PSA.

Should I wear a mask?

In general, no. Regular surgical masks stop droplets, which is helpful but won’t filter out viruses. If you are healthy and out in public, you don’t need one. N 95 respirators, masks that can block 95% of particles down to 0.3 microns, are used by people exposed to dust and other small particles. Health care N-95 respirators are a subset, specifically for health care workers. They need to be fitted to be effective and are a bitch to breathe through.

You should wear a mask if:

- You are a health care worker.

- You are coughing or sneezing.

- You are sick and need to leave the house

- You are sick and can’t isolate yourself from healthy housemates

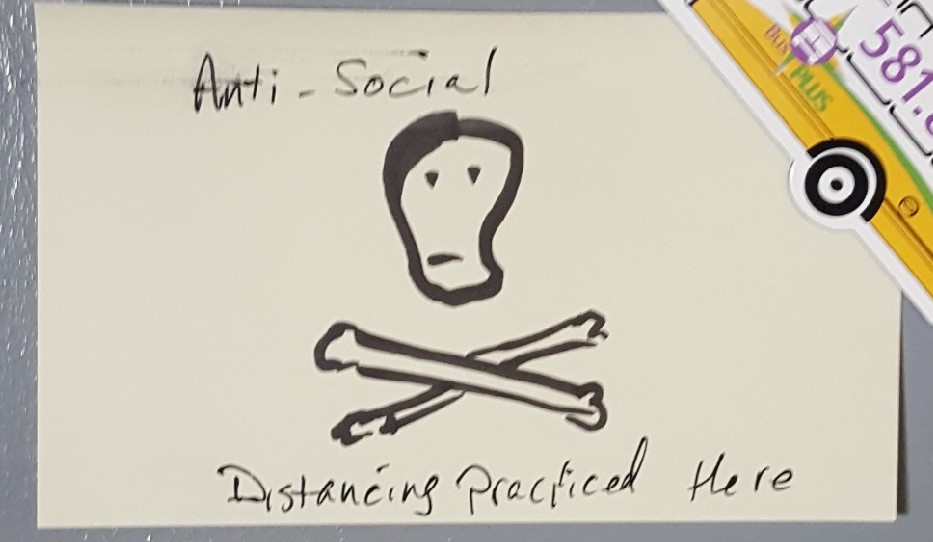

Why should we practice “social distancing?”

Because health officials want to avoid an exponential increase in coronavirus cases by “flattening the curve.” (If you don’t understand exponents, you weren’t paying attention in algebra class and I don’t have time to explain them! Just think “increasing really fast.”) We don’t want a lot of people getting sick in a short period of time and overwhelming the health care system. It is better to spread out those illnesses over many weeks or months.

Protecting the vulnerable – those who are elderly or have compromised immune systems – is the single best reason for keeping your distance from other people.

How is COVID-19 treated?

Like any other viral illness there is NO cure. One treats the symptoms whether cough, fever or full-blown respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. Influenza is often treated with oseltamivir, which shortens recovery by 1 to 2 days. Remdesivir, created from a molecule developed ten years ago, may be the best drug to treat COVID-19, but it’s only in the testing stage and it isn’t a cure.

Eating garlic, drinking bleach or colloidal silver, breathing hot air from your hair dryer, taking Vitamin C or zinc, snorting cocaine or masturbating will not protect you from COVID-19.

Related: Buzzfeed News list of coronavirus hoaxes

What should I do if I feel sick?

If you just feel crappy with mild to moderate viral symptoms – cough, fever, aching – call your healthcare provider. DO NOT go to the Emergency Room without being told to! They don’t want to see your sorry ass for something that is not life-threatening and will just have to run its course.

However, if you are having chest pain or enough difficulty breathing that your lips are turning blue, or you feel as if you are drowning, GO TO THE EMERGENCY ROOM IMMEDIATELY!

Should I be tested?

Not unless a qualified healthcare worker thinks you need to be tested.

There aren’t enough tests right now.

Where should I go for information?

- The Centers for Disease Control

- Your state’s Departments of Public Health

- Harvard Medical School’s Coronavirus Resource Center

DON’T PANIC. DON’T BE STUPID. BE CAREFUL.

Coronavirus illustration © Can Stock Photo / feelartphoto