A pregnancy starts when a Fallopian tube sweeps up an egg like a shop vac and sends it down towards an army of sperm lying in wait. While it takes one sperm to fertilize an egg, it takes hundreds of them to break down the zona pellucida, the egg’s barrier to fertilization.

When that happens, the lucky bastard yells, “I’ve got you now, my pretty,” and thrusts himself into her. Now joined in holy matrimony, the fertilized egg – a zygote – takes a short honeymoon trek down the tube, developing into a blastocyst on its way the uterus. There it implants, sets up housekeeping and watches Netflix for the next nine months.

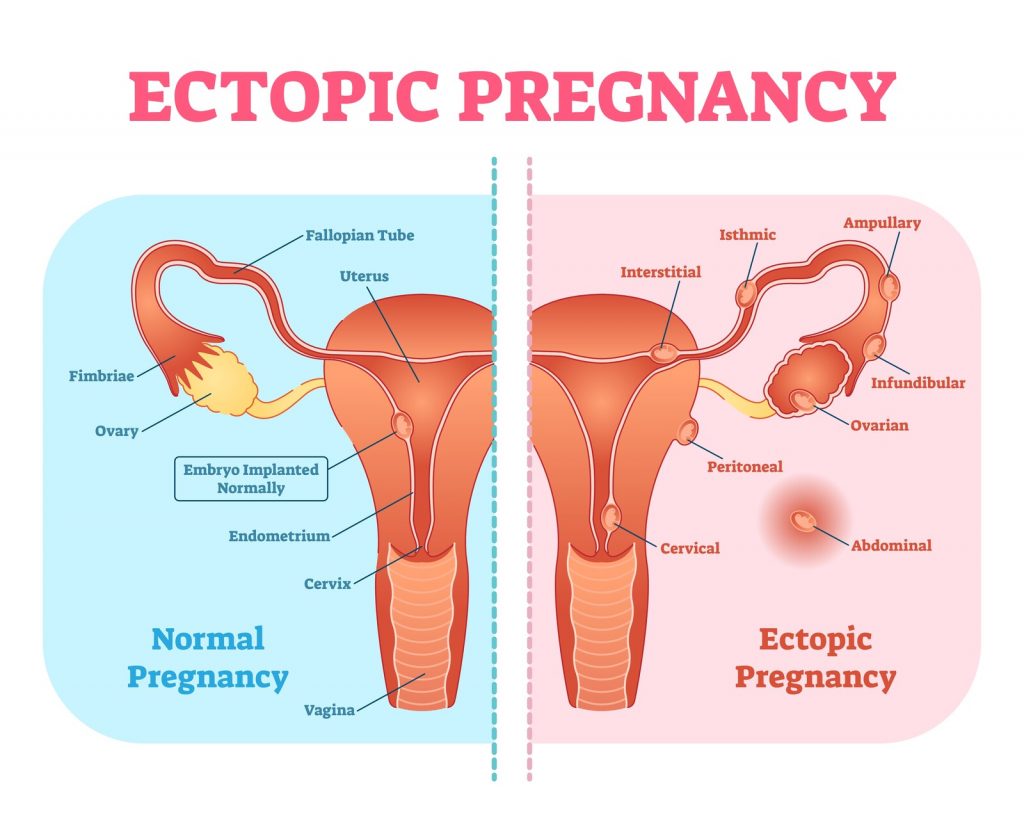

But that doesn’t always work that way. The blastocyst may attach itself somewhere outside the uterus in an “ectopic” location that wasn’t designed to grow a full-term baby. Those sites include the Fallopian tube (the most common); the cornua (where the tube attaches to the uterus); the cervix; an ovary or inside the abdomen.

An ectopically implanted pregnancy is more likely in a woman whose tubes have been damaged by infection, endometriosis, or previous abdominal surgery, including tubal ligation. Using an IUD for contraception increases a woman’s risk. Even a woman who has had a hysterectomy but with an intact ovary can become pregnant, likely earning her a place in the tabloids.

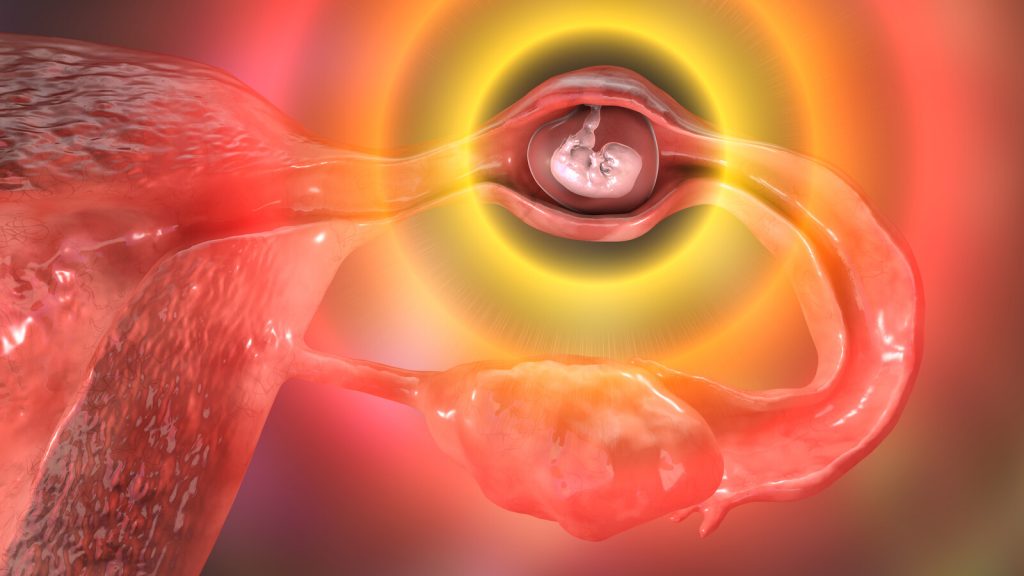

An abnormally implanted pregnancy can only grow so much before the tissue around the implantation site blows apart and all hell breaks loose. Internal bleeding can be massive and a woman will die from hemorrhagic shock if not treated promptly.

The Arab Spanish physician Abulcasis (Arabic name: Abul Qasim Khalaf ibn al-Abbas al-Zahrawi al-Ansari), was an impressive and accomplished dude who wrote Al Tasrif, a thirty volume medical encyclopedia, earning him a place among the “fathers of surgery.” He made the first known reference to ectopic pregnancy in the 10th century. Other physicians reported ectopic pregnancies during the next 900 years, largely discovered at autopsy as it was invariable fatal.

But by the mid 1800’s doctors were becoming more aware of the signs and symptoms of ectopic pregnancy. Timely surgical intervention saved the lives of many women but definitively differentiating an ectopic pregnancy from other conditions – an ovarian cyst, endometriosis, or appendicitis – remained problematic for the next 100+ years.

Such was the state of diagnostic abilities when I started my residency in 1979. A woman who came to the Emergency Room in obvious hemorrhagic shock – high pulse and low blood pressure – went straight to surgery. But if she presented with lower abdominal pain, a positive pregnancy test and sometimes brown vaginal bleeding – and was hemodynamically stable – we tried our best to confirm an ectopic pregnancy. The probability increased if, on pelvic examination, one felt a painful mass on either side of a normal-sized uterus, but there was still a 20% chance it was something else.

Ultrasound had been used clinically since the mid-1950s, but images weren’t great, appearing more like abstract paintings than pelvic organs. Radiologists’ interpretations were often ambiguous and usually unreliable when proclaimed with absolute certainty. One of my attending physicians opened up a woman’s abdomen after the radiologist said, “There is definitely an ectopic pregnancy here,” only to find absolutely nothing.

If we were still unsure and the woman agreed to it, we’d try doing a culdocentesis. That involved sticking an 18-gauge needle through the back of the vagina below the cervix, then pulling back on the plunger of a large syringe. (Yes, it’s as painful as it sounds, even after injecting local anesthetic into the area.) Sometimes we were lucky. If the syringe filled with “non-clotting” blood (blood that had already clotted and then broken down), we knew she was bleeding internally and likely had a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. If culdocentesis wasn’t successful and we still weren’t sure, we took the woman to the operating room for diagnostic laparoscopy sparing the woman an abdominal incision if everything looked clean.

Tubal pregnancies are usually dark purple blobs, ranging in size from a pomegranate seed to a breakfast sausage, which may be leaking a little blood or actively hemorrhaging. There’s usually a small piece of placental tissue among the clot in the tube, but nothing that remotely resembles a fetus. I witnessed one notable exception during my residency. A tiny, live fetus, about the size of a grain of rice, was moving in the small gestational sac that had been expelled from the end of the tube. And no, there was – and still – no way to implant it into the uterus! Placental tissue, once disrupted, won’t reattach itself in the uterus.

We had three surgical options:

- Opening the tube over the affected area, emptying out the contents and delicately sewing the incision shut, making sure there was no bleeding. The tissue was fragile and it was like sewing two sticks of room temperature butter together.

- Taking out the damaged section of tube, leaving the ends for a skilled microsurgeon to put back together later on.

- Taking out the entire tube because a badly-damaged tube made another ectopic pregnancy more likely.

A lot has changed since I started residency more than forty years ago.

Diagnostic testing

Simple urine or blood pregnancy tests, first developed in 1976 and referred to as “qualitative”, look for the presence or absence of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) a hormone produced by placental tissue. A positive test indicates a pregnancy somewhere in a woman’s body. A negative test usually means there is no pregnancy but the test will be “falsely negative” if hormone levels are too low to detect.

Structurally, hCG is made up of two pieces: the alpha subunit (α-hCG) which is also common to ovarian and thyroid hormones, and the unique beta subunit (β-hCG). Starting in the early 1980s, laboratories were able to assay blood for small amounts of this beta unit, the “quantitative β-hCG test.” We used the changes in hormone level over several days to monitor very early pregnancy development, hoping to distinguish normal pregnancies (single and multiple) from abnormal ones (blighted ovum, miscarriage, ectopic, the varied forms of molar pregnancy, or placental fragments leftover in the uterus after a miscarriage).

Measured in milli-International Units per milliliter (mIU/mL), hCG becomes detectable around the third week after a missed menstrual period. hCG levels should double every 48 hours in a normal pregnancy and transvaginal ultrasound should be able detect a gestational sac in the uterus at around 1,500-2,000 mIU/mL. One can reliably rule out an ectopic pregnancy after detecting a fetal pole (the earliest evidence of a developing embryo) with a heartbeat. (Simultaneous intrauterine and ectopic pregnancies occur spontaneously in less than 1:30,000 naturally occurring pregnancies, but that incidence increases to 1:100 to 1:500 with in vitro fertilization.)

hCG levels that rise more slowly, plateau or decline usually indicate an abnormal pregnancy. Combined with serial ultrasound examinations will lead to diagnosing:

- A blighted ovum if there is an empty gestational sac with no fetal pole;

- An inevitable miscarriage if there is a fetal pole larger than 7mm with no heartbeat

- A miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy if there is only placental tissue in the uterus at levels where we would expect to see a gestational sac.

If physicians can’t rule out an ectopic pregnancy, they’ll scrape tissue out of the uterus (a D&C) and ask the hospital pathology department to look at the tissue while still in the operating room. If there’s only endometrial tissue and no chorionic villi, the vascular bridge between the uterus and placenta, there’s an ectopic lurking somewhere.

Imaging

Ultrasound image resolution has progressed from vague static images like this:

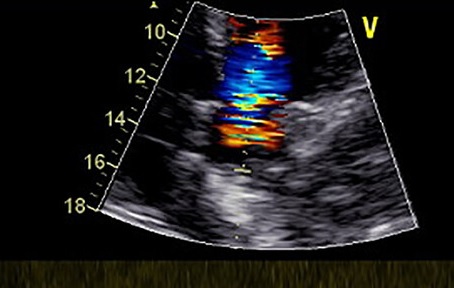

to detailed, real-time images such as this fetus (the four lines in the black area is the umbilical cord).

Color flow Doppler ultrasound can show blood moving in and out of an ectopic pregnancy in the adnexa, the area next to the uterus, which is helpful if the sonographer can’t distinguish a definite mass. (This, however, is Doppler flow of a heart, the only royalty-free image I could find.)

So, when a radiologist tells me, “There’s a 2cm mass with blood flow in the right adnexa, nothing but endometrial tissue in the uterus and a lot of echogenic material in the cul-de-sac running up the para-colic gutter,” I know I can skip the laparoscopy and open her up.

Surgical treatment

However, surgical treatment has also changed. Tubal ligation was the only surgical procedure we did in the early 1980s. By the early 1990s, physicians with far more balls than me, along with surgical instrument innovations, were starting to take things out of people laparoscopically. Removing an inflamed appendix became a simple outpatient procedure. Taking out a gallbladder full of stones using a laparoscope was far easier and less traumatic than the old days which required an incision along the right rib cage from stem to stern, and digging deep while your poor intern (me) tried to retract a six-inch deep wall of fat with a “Weinberg Vagotomy Retractor,” otherwise known as Joe’s Hoe (and it is as big as the garden tool).

“Pull harder, dammit!”

“I’m pulling as hard as I can!”

Operative laparoscopic surgery had a steep learning curve in the early days and I was skeptical of the newfangled approach to ectopic pregnancy. I was suckered into assisting two youngsters with far more confidence than ability and both endeavors lasted two hours. One insisted in putting a trocar (which looks like a tent stake) through the abdomen in the vicinity of the inferior epigastric artery, despite my pleas to reconsider. She wasn’t concerned with the pulsating stream of blood and continued prospecting for the ectopic pregnancy.

I got a call one Saturday at midnight from the ER doc at a small hospital in Nebraska, 70 miles away from where I was working.

“I have a woman here with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy and I want to transfer her.”

“You don’t have anyone there who can deal with it?”

“Well, the general surgeon comes here on Wednesdays but I don’t think she’ll hold out until then. I’ve started a unit of blood and the ambulance is here.”

I was working as a locum tenens in someone else’s practice. I called the senior partner since he was rather protective of the practice’s reputation and I didn’t want to step on any toes. He wasn’t happy but met me in the Emergency Room. The woman arrived about 1:30am and, after introductions, examination and discussion, we were in the operating room at about 2:00am.

Setting up for an operative laparoscopy takes at least half an hour or more after the patient goes to sleep. The equipment includes:

- a video camera and two monitors

- the laparoscope light source

- the CO2 insufflator used to blow up the abdomen like a balloon so the surgeon has room to work

- an electrocautery unit

- reusable instruments like the laparoscope and the insufflation needle

- an array of expensive, disposable stuff like operating ports, instruments to cauterize vascular pedicles, a combination irrigation/suction device hooked up to room suction and a bag of saline,

- and a uterine manipulator, which requires putting the woman in stirrups, putting on the surgical drapes, using a speculum to find and dilate the cervix before inserting it into the uterine cavity.

Laparoscopic surgery starts with putting in the insufflating needle just inside the belly button, the thinnest part of the abdominal wall, then filling the abdomen with enough CO2 so there’s room enough to work. After that, the surgeon inserts at least three or four ports in the abdomen: a 10mm for the laparoscope; a 5mm just above the pubic bone for a wand to move the innards around; and 5mm or 7.5mm ports on either side for operating instruments and grasping. (I have six abdominal scars from my robotic prostatectomy.) Click here for a great overview of laparoscopic trocar placement.

Older ports consisted of a stainless steel trocar with a pyramidal end like a tent stake inside a stainless steel sleeve which one pushed this through small incisions, taking care not to puncture the bowel, the bladder or the aorta. Newer ports are disposable plastic with more blunt trocars to minimize the chance of damage, but they take a little longer to work through the abdominal wall.

So, after setting up, gently and deliberately excising the damaged portion of tube, sucking out blood and clot, irrigating the pelvis, inspecting to make sure everything is clean and hemostatic, taking all the instruments out and closing the incisions, we were done about 90 minutes later.

My approach to an ectopic pregnancy in the good old days was direct. I’d make a small abdominal incision, grab the tube with a Babcock clamp, remove the offending ectopic, clean out the blood and clots in the pelvis, inspect the other tube and ovary, and then close her up in 20-30 minutes.

It’s one of many reasons I’m happy to pass the baton to a younger generation.

Medical Treatment

Methotrexate, a drug initially used to treat cancer and then rheumatoid arthritis, is sometimes used to treat unruptured ectopic pregnancy. There are stringent criteria for its use – a stable and reliable patient, a mass less than 3.5cm, hCG < 5,000 mIU/ml, and no detectable cardiac activity – and the woman must be monitored closely with serial hCG levels. Success rates are reported to be around 90% when used appropriately.

The emergency room physician at a small hospital in Tennessee called me around 11:30 pm on a Sunday night. A 42-year-old woman came in complaining of vaginal bleeding for a week and severe pain in her right lower abdomen. “She has a positive pregnancy test; her hemoglobin is 8 and her pulse is about 110.” A normal hemoglobin level for a non-pregnant woman is 12-16 gm/dl; even in pregnancy the level should be 11 or so.

I walked into the examination room and met a slightly pale woman on a gurney; her husband stood next to her.

“Hi I’m Dr. Rivera. I assume the ER doc has told you why I’m here?”

“Yes, he told me I’m going to need surgery.”

“Well, that’s a good place to start. Tell me what’s been going on.”

“I started bleeding off and on last Monday. I didn’t think much of it, but it hasn’t stopped, and I started having pain in my side tonight, so I came here.”

“Have you felt any pain in your shoulders?”

“Yes, my right shoulder started hurting two days ago.”

She noticed the look on my face and asked, “That’s not good, is it?”

“Not really. If you’ve had internal bleeding the blood can irritate your diaphragm and your body interprets that as shoulder pain.”

“Yes, but how can I be pregnant? I had my tubes tied thirteen years ago!”

“Well, tubal ligations have an inherent failure rate. I saw one woman who got pregnant after her tubal. I took out her tubes after delivery and found an inch gap in both tubes.”

“Really!”

So I took her to the operating room. My scrub tech was the Czechoslovakian grandmother who always made sure I was well-fed when I made rounds in the morning. I was sure I didn’t need to start with a diagnostic laparoscopy and went straight to an abdominal incision. She had 1300cc of blood and clot in her abdomen from a ruptured ectopic; I took out what was left of both Fallopian tubes. By now she should be menopausal and safe from that sort of misadventure.

For all the progress we’ve made, some want to turn back the clock. Some Right-to-Life types have conflated treating an ectopic pregnancy with abortion, saying intervention isn’t necessary. The author of that article has since apologized, but the damage has already been done and such misinformation has already spread.

Graphics © Can Stock Photo

Explosion: Jag_cz

Fertilization: stockdevil

Ectopic Sites: normaals

Ectopic: Kateryna_Kon

Fetal Sonogram: faustasyan

Doppler: faustasyan