I have something in common with Ian McKellan, Robert DeNiro, Colin Powell, Mandy Patinkin, Warren Buffett, and the Grateful Dead’s Phil Lesh. We’ve all had prostate cancer.

You might ask, “What is the prostate and what does it do?” Well, since you didn’t ask, I’m going to tell you anyway.

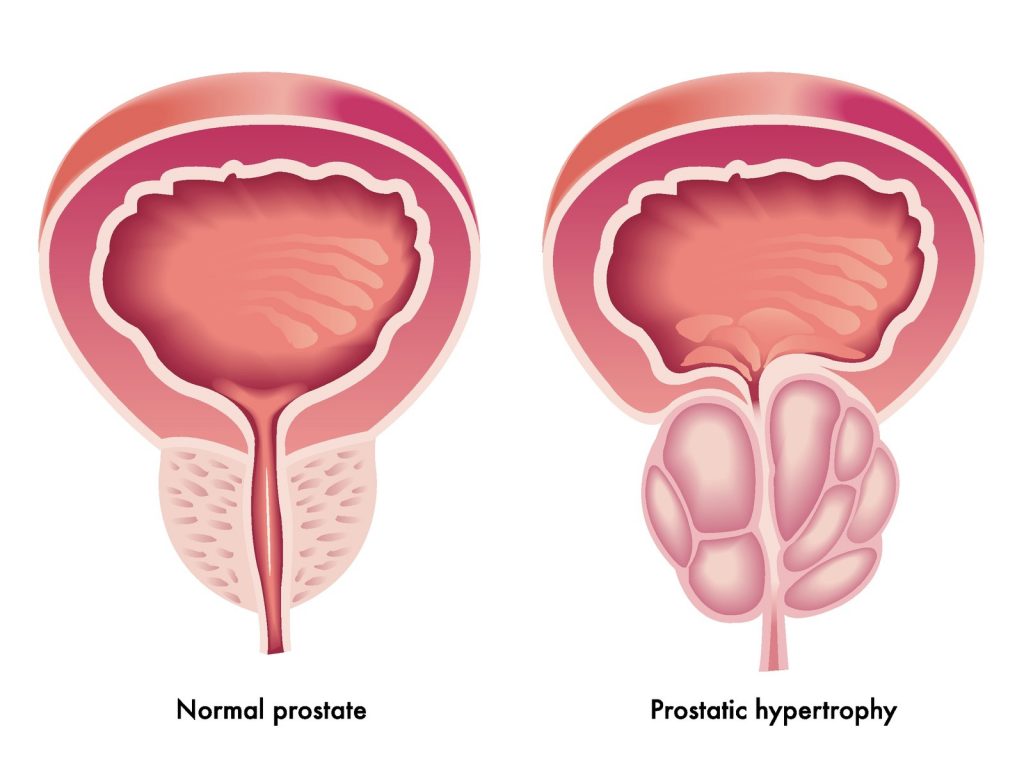

The prostate is both a blessing and a curse. Located just below the bladder, the prostate is a collection of muscular glands surrounding part of the urethra, that tube running from the bladder and through the penis to the outside. It has been compared in size to a small apricot. It secretes fluid containing zinc, citric acid and some enzymes which act as a sort of Miracle-Gro® for sperm, aiding in the quest to be the one lucky bastard that fertilizes the egg to create a pregnancy.

The prostate also provides an endless source for amusement for urologists hell-bent on pimping medical students. It works like this. The urologist asks the student to perform a rectal exam on a male patient and describe the impression, then sneer and say, “He’s had a prostatectomy. So, what were you feeling, “doctor?”

However, in our later years, the prostate often enlarges and squeezes the urethra, a condition known as Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy, or BPH. It turns a urine stream rivaling that of a firehose into an annoying dribble that usually ends in our underwear.

Back in the Dark Ages (more than 30 years ago), we treated BPH with a ghastly procedure known as Transurethral Resection of the Prostate or “TURP.” A surgeon would put a resectoscope, a lighted tube with a wire-loop cautery at the end, through the penis and drag the prostate out in pieces. I remember seeing men in the recovery room hooked up to 3-liter bags of irrigating fluid to flush out blood and chunks of well-done prostate.

Now we have a group of drugs called alpha-blockers (tamsulosin and others) which make urinating a lot easier. They still don’t make up for the overly large prostate compressing the bladder, which makes us pee a lot during the day and get up two or more times during the night.

The prostate also produces Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA), an enzyme that changes semen’s consistency from Elmer’s glue to runny-nose mucus. Measuring PSA in a blood sample is a screening test for prostate cancer; a “normal” value is < 4.0 ng/ml. A value above 10 ng/ml means a 50% chance of prostate cancer. A PSA value of 4.0-10 ng/ml is concerning and often means monitoring more often than yearly.

PSA testing has some of the same limitations as other screening tests. Remember when Gene Wilder promoted CA-125 screening after Gilda Radner died from ovarian cancer? CA-125 only picks up half of Stage I ovarian cancers, and CA-125 can be high with endometriosis, early pregnancy, ovarian cysts and pelvic infection. I had a patient who died of metastatic ovarian cancer with normal CA-125 levels.

A normal PSA doesn’t mean you don’t have cancer, while a high PSA doesn’t mean you do, since levels can increase with BPH, infections and ejaculation within 48 hours of testing. A man I know has been living with elevated PSAs for years despite negative MRIs and biopsies.

I’ve been getting annual PSA checks since 2007, which had been 1.0 ng/ml or less through 2017. It was 1.5 ng/ml in early 2018, but my prostate was larger and neither my urologist, Dr. Li K?, nor I were worried.

However, my level in March 2019 was 2.7 ng/ml. Even though this result was technically “within the normal range,” I couldn’t rationalize an increase this high. Dr. K? agreed and recommended a repeat test in six months (September).

Knowing the health care system often moves slowly, and mindful of the fact that the end of the year (and our deductible limit) was approaching, I got another sample in August, opting for both total (circulating PSA bound to proteins in the blood) and free (PSA wandering merrily by itself like an unaccompanied child) levels. The percentage of free PSA can predict which men with levels between 4 and 10 will likely need biopsies to detect cancer. The higher the percentage, the lower the risk.

May I have the envelope, please? (Drum roll)

| PSA, total | 4.4 ng/ml |

| PSA, free | 0.4 ng/ml |

| % total/free | 9 |

| Probability of cancer | 56% |

Well, shit. I sent the results to Dr. K?.

“I want you to get an MRI at our facility. I know our radiologists and trust them.”

I texted my kids with the news, shamelessly figuring it might get their attention as they rarely contact me about anything. It did. No one actually called, but they did text me replies, the communication choice of Millennials everywhere.

“Is there anything you need?”

“How bad is it?”

“Am I in your will?”

No one texted that last one but I’m willing to bet it was in the back of someone’s mind.

The MRI

An MRI is something everyone should experience once, like visiting Graceland, then check it off the bucket list. Have another go at it? No, thanks, I’m good.

I had my MRI the day before my 65th birthday. Imagine stuffing a bratwurst inside a cannoli tube and then loudly banging on a variety of metal objects, at varying tempos, for an hour while telling the bratwurst to lay still. Oh, and we’re going to roast you low and slow.

The earplugs they provided did little to block the noise. A sleep mask would have been more helpful as the top of the machine was about 2 inches from my eyeballs, a bit unsettling even though I’m not normally claustrophobic. I started getting really warm about thirty minutes into the procedure. I complained to the tech who said, “We’re almost done. Just a few more minutes.”

Yeah, right.

Finally, it was over. The tech helped me off the table and said I should get results in 1-2 business days. That was on Tuesday, but I hadn’t heard anything by Friday.

Peg asked, “So, are you going to call them? This is ridiculous. It’s been three days.”

I said nothing.

“So, you think no news is good news?”

“Pretty much.”

On Saturday I got a text message, “You have new test results!” from MyChart, an electronic health record application and one of the few things Epic has done right. My MRI result was posted, and I figured it must be good news since no one had called me. Wrong.

“IMPRESSION: Overall PI-RADS 4: Clinically significant prostate cancer likely within the left posteriolateral peripheral zone.

FINDINGS:

PROSTATE:

Size: 33cc, 4.4 x 3.9 x 3.8cm in the greatest transverse, AP and craniocaudal dimensions. Central zone/transitional zone: There are multiple nodules of varying signal intensity on T2 weighted imaging within the central-transitional zone in an appearance consistent with benign prostatic hypertrophy.

(No shit, Sherlock.)

Peripheral zone: Oblong ill-defined 1.2 x 0.8 cm lesion within the left posteriolateral peripheral zone at the base and mid gland demonstrating markedly hypointense signal…Mild capsular abutment without extraprostatic extension.”

(Translation: You have a tumor about the size of a small blueberry in your apricot and that’s not good.)

Most physicians have had to give patients bad news during their careers, but it’s a bit different when you’re on the receiving end. I wasn’t surprised given the relative rapid rise in my PSA and the probability given on my last test. Still, I stared at the screen for several minutes before printing the report and giving it to Peg.

She was livid.

“No one should get a cancer diagnosis without a phone call from a physician! What if you were someone with no medical background?”

Well, I can’t argue with that.

Sometimes I’ve merely confirmed what patients had already been suspecting. One was a woman I met during one of my locum tenens jobs. I curetted her uterus for heavy bleeding and knew she had cancer just by the tissue’s appearance. A few days later I asked her to come to the office to talk about the results. She had an aggressive endometrial stroma sarcoma that would end her life in less than a year. The irony of working in hospice with terminally ill patients was not lost on her. She was calmer than I would have expected, but I didn’t know what she might have felt in the following weeks.

Peg found my lack of response unsettling.

“Are you not saying anything because you’re worried?”

“Not really. I’m processing. Would you like me to be hysterical?”

“No, I just want you to react! At least say something.”

I didn’t say much to Peg about the probability of having cancer. Maybe it was the physician in me that was used to dealing objectively with bad news. And it was somewhat perplexing as I figured my crappy lungs would eventually do me in.

I texted my kids again with the MRI results and that I’d need biopsies. Number two son said, “Well, if you have to have cancer, it’s good to have the boring kind.”

My eldest texted back, asking if the cancer had spread. Using talk-to-text, I said, “Nodes and pelvis are clear,” which it changed to “Nodes and Elvis is queer.” Gotta love technology.

I was looking for a client’s house somewhere in the northwestern part of Chicago when the office called to set up prostate biopsies. I’d already made an appointment for the following Wednesday to discuss the MRI results, so the scheduler changed the appointment to the procedure. She also said I had to take Thursday and Friday off.

I sent an email to my handler. “I need to take off next Thursday and Friday. I’m having a procedure done and I need to lay low for a couple of days.”

He replied: “How long have you known about this procedure? I need a lot more notice to move things around. I can’t just move things around so easily.”

Ok, wiseass, I was trying to be discrete. Now I’ll be blunt.

“I just found out about it yesterday while driving around Chicago. I had an MRI last week that indicates probable prostate cancer. They called to set up an appointment for biopsies.”

Silence for several hours. Then: “understood.”

Prostate biopsies are usually done transrectally (through the rectum). The urologist inserts an ultrasound transducer into the rectum, then passes a spring-loaded biopsy needle through a guide and takes several samples, using the ultrasound image for guidance.

The only thing that produces pain in the large intestine is distension (you can clamp, cut, or stitch it with impunity), so, poking a needle through the rectal wall isn’t terribly uncomfortable. Injecting local anesthetic into the prostate produces a familiar pinching sensation, but it doesn’t burn as it does when injected into skin. And it’s much less painful than the old transperineal route, which required an incision between the scrotum and anus, known colloquially as “the taint,” and often done under general anesthesia.

Peg and I arrived early for my 5 p.m. appointment but then sat for 45 minutes in a nearly empty waiting room. The reason for that will become apparent in Part 2.

When we were finally granted access to the inner sanctum, Dr. K?’s nurse led me to the procedure room. The first thing I noticed was an instrument stand covered with a sterile drape on which sat several small containers filled with Formalin, a long needle attached to a syringe, and something that looked like a light sabre handle with a needle sticking out of the business end. She told me to take my pants off and put on the exam gown which barely covered my ass.

After Dr. K? engaged in the usual pre-procedure pleasantries, I lay on my left side on a very uncomfortable examination table, then she inserted the ultrasound transducer through my anal sphincter and halfway to my tonsils. It’s like using a butt-plug with fangs, with none of the erotic sensation.

“First I’m going to inject local into the right side of your prostate.” About thirty seconds later, she said, “Now the left side.” She waited a few minutes for the lidocaine to do its thing before she started sampling.

The biopsy instrument is a very fine, spring-loaded needle that snaps when one pulls the trigger, capturing a piece of prostate tissue. It’s less noticeable than the anesthetic injection, but still made me wince slightly every time I felt that snap. I lay still and listened as she called out the locations to her assistant, who put the pieces into the small containers.

“Left apex.” *snap* (wince)

“Left mid.” *snap* (wince)

“Left base.” *snap* (wince)

“Right apex.” *snap* (wince)

“Right mid.” *snap* (wince)

“Right base.” *snap* (wince)

She told me to expect blood in my urine and stool for a couple of days and to call if I started passing clots. Clots???

“I’m going to call you with the results before I release them to MyChart.” (You’d better or Peg will have your neck. )

I made a follow up appointment for two weeks later.

My urine was slightly pink that night, but yellow the next morning, like a fine chardonnay. The only rectal bleeding was from an irksome hemorrhoid. Yeah, getting old sucks. I think I could have easily gone back to work, but I welcomed the break.

Dr. K? called me a few days later to tell me she’d received the pathology report; it was what we’d both expected.

Biopsy pathology report

Prostate needle core biopsy, right base:

-Atypical Small Acinar Proliferative (ASAP), in one of two cores

Prostate needle core biopsy, left mid:

-Adenocarcinoma of prostate, Gleason 4 + 3 = 7 (Grade Group 3)

–Tumor in 1 of 2 cores, tumor length 1mm, discontinuously involving 5% of submitted tissue.

Pathologists grade tumor cells based on how abnormal they appear under a microscope. Prostate cancer cell grades number 1 through 5 with five being the worst. The Gleason Score takes first and second most predominant grades and adds them together. The least malignant score is 2 (1+1) while the most malignant is 10 (5+5). A Gleason score of 4+3 is worse than a score of 3+4, even though the sum of both is 7.

I’d considered radiation treatment as the lesser of the evils but the small amount of tumor in the biopsy relative to the size of the lesion, along with the “atypical” cells on the right side convinced me surgery was the better approach. I like having tumors in a jar; surgical specimen pathology is often more severe than the biopsies.

We saw Dr. K? the following week to discuss options, but I’d already settled on surgery. The problem with doing radiation first is that if the cancer recurs, surgery is nearly impossible because radiation has turned the prostate into mush, and you’re screwed. If you have surgery first, radiation is available if the cancer comes back.

There are considerable risks to radiation: difficult or painful urination; diarrhea, bowel cramping, fatigue, “sunburn” on abdominal skin, and the possibility of developing cancer in bladder or bowel. A Facebook buddy undergoing radiation for colon cancer told me “may I suggest rather than using the very pleasant descriptor, “you may experience occasional diarrhea” with “by week three you will have come to believe you’ve eaten and (sic) entire jar of jalapeños and are pissing pure lemon juice.”

Dr. K?, being a general urologist gave us the names of two colleagues, Dr. Fine. and Dr. Howard, both of whom specialize in robotic radical prostatectomy. Peg caught her off guard asking, “Who would you personally go to and who has the better bedside manner?” She replied without hesitation. “Dr. Fine.”

I made an appointment with Dr. Fine for the following week.

Next month: To Surgery, and Beyond!

Apricot: © Can Stock Photo / Tigatelu

Prostate © Can Stock Photo / rob3000